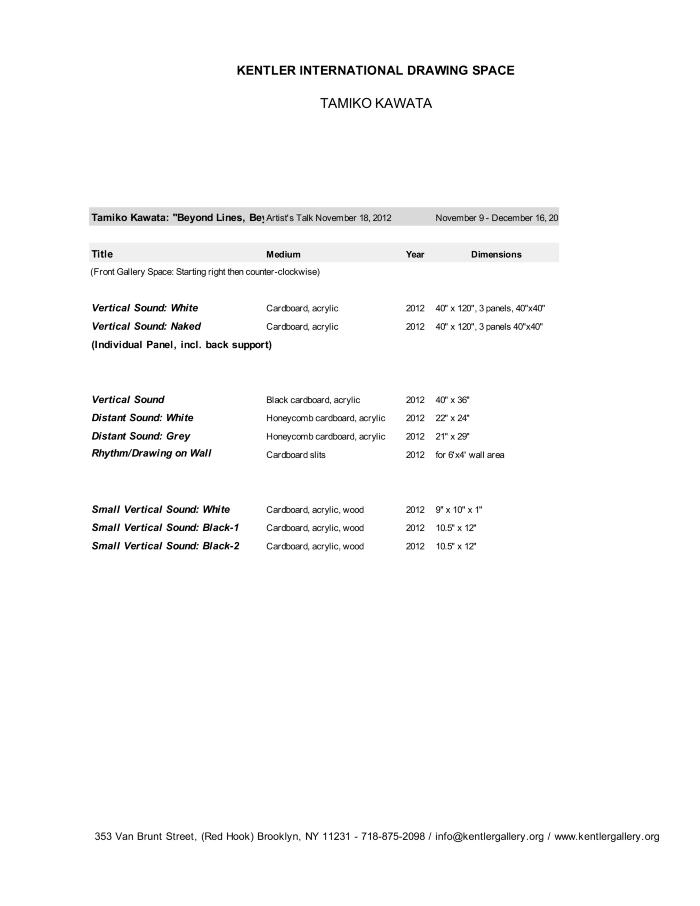

exhibition

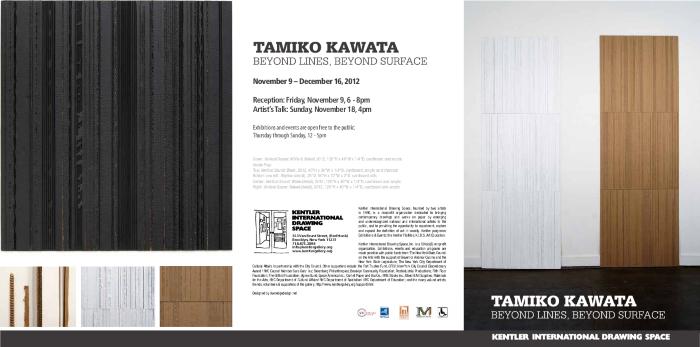

Tamiko Kawata, Beyond Lines, Beyond Surface

Date

November 9 – December 16, 2012Opening Reception

November 9, 2012Essay By

David BrodyArtist

Tamiko KawataRelated exhibition

Joan Grubin, Paper OpticsRelated event

Artist's Talk: Tamiko Kawataexhibition Images

Click to Enlarge.

Press and Promotion

About the exhibition

Solo exhibition, front gallery space

ARTISTS' TALK:

Sunday, November 18, 4pm

On one wall at the Kentler International Drawing Space, Tamiko Kawata cuts, scores, gouges, tears and peels the smooth surface of two-ply, corrugated cardboard to reveal, to a greater or lesser extent, its corduroyed interior grain. Across the way, she slices the same material into hundreds of thin strips against the grain, producing delicately trussed cross sections, which she weaves on the wall in a busy vertical current. One installation crackles, the other ripples with linear energy, and both exemplify how Kawata’s structuralist approach––her methodical unearthing of the hidden properties and textures of a chosen material––can lead to sly commentary or urgent metaphor. At Kentler the fluted piece, Vertical Sound: Black & White, starts with the formal and gets all the way to the primal. It begins by reenacting the raked concrete of brutalist architecture, but so cannily as to remake minimalist stripe painting in the process; yet the violent, impulsive flagellation of the cardboard’s surface reads equally as tender wounds of the skin, maybe wounds of the soul.

Besides cardboard, Kawata has made exhaustive use of a variety of stockroom supplies and surplus materials, from bubble wrap to used pantyhose, but she is most widely known as a sculptor of safety pins, interlinking masses of them into improbable configurations. It’s worth noting that she prefers, when listing her materials, the term “metal” to “safety pins,” coyly deflecting attention from meanings already loaded into the object––e.g., a painful sharpness set to spring; the dawn and dusk of American mass production; and of course, domestic chores––in favor of those that emerge along the path of her transformations. A feminist consciousness of the safety pin’s status certainly remains active in these works (we’ll come back to this later), but somewhat at second hand––which is only natural, given that in Kawata’s native Japan tucking and folding is the rule; no one would think to spike a diaper or to pierce fine fabric. Thus Kawata never used a safety pin until immigrating to America in 1962, discovering their utility, first, when American clothes turned out to be too big for her.

But one evening Kawata found herself having to dress, atypically, for the kind of party where women wear fancy jewelry. She turned to arrangements of safety pins for witty, proto-punk versions of necklaces and earrings. That these basic clasps were cheap and small, and could be worked while tending her two young children, impressed itself upon Kawata, who lacked money, space, and time for sculpture. Moreover, her experiment with wearable art had created luxury demand––ironically, considering their proletarian edge––helping to support her studio practice.

With the jewelry, Kawata had begun to explore the pins’ combinatorial potential, and soon she was interweaving thousands of them into flexible mats, meshes, and tangles––composites that Kawata could now utilize as primary materials. Perhaps this layer of remove allowed a new plainspokenness in her imagery. Her safety pin installations were soon suggesting tatami: Japanese mats that modularized and abstracted the home centuries before Corbusier. Others poured from the wall like a waterfall, or a veil of tears, or industrial outflow, or pooled on the floor in meditative spirals.

Hanging chains of pins allowed her to write a long-delayed letter in jangly columns of mute characters; it was to her mother, who had disowned Kawata for emigrating to pursue her calling.

And lastly, a particular structural felicity has enabled a whole family of safety pin works: serpents, forests, mushrooms, crowds, gravestones, cocoons, anemones––and phalluses. As for the intriguing connotations of these images, whether geometric or biophilic, mythic or political, let’s defer for a moment to appreciate their tubular technique; from that angle we may be able to sneak up on Kawata’s iconography.

The helices that Kawata constructs out of safety pins arise from a chain of cumulative displacement, until the mesh comes seamlessly full circle and links with itself, like snakeskin. That Kawata engineered this phase change from two to three dimensions in her pin structures is formidable, a mathematical-aesthetic insight in the same province as DNA visualization, tensegrity, or geodesics. If you doubt that, look at how Kawata’s criss-cross beehive spirals, which she has been playing with for decades, prophecy Norman Foster’s “Gherkin” building, his British Museum atrium, and others of his 21st-century projects. (Kawata’s husband is a British-born architect. Might Foster have crossed paths with a Kawata installation?) It is no shock to learn that Kawata’s father, speaking of DNA, was a professor of mathematics, the author of textbooks that became international standards on wave analysis and permutation––subjects clearly resonant with Kawata’s sculptural toolkit. For many artists, mathematics is impossible to fathom and, moreover, anathema to creative freedom––the “cogs tyrannic, moving by compulsion” of Blake’s clockwork Newtonian hell. The opposite is true for Kawata; mathematical thinking is the family business, neither obscure nor coercive, but fully creative in its own right.

Father and daughter were close. The mathematician supported his daughter’s unconventional desire to study art––and indeed, it was unconventional for a woman to be allowed to pursue higher education at all in postwar Japan. More liberal yet, Kawata’s father approved her joining a mountain-climbing club as the only female member, an almost inconceivable freedom for a young Japanese woman of “respectable” family.

Mountain climbing changed Kawata’s understanding of nature and altered the course of her art. The world above the trees was stripped bare, the structure of reality disclosed. By comparison, Kawata explains, the kind of painting she was studying came to seem “soft,” “philosophical,” a kind of inconclusive dithering. A Bauhaus-influenced design teacher helped her break free of the School of Paris figuration that dominated art departments in Japan somewhat longer than in America. Design thinking led her, instead, to an abstraction of system and method; of materials subject to gravity, spatial logic, and their own capacities. To Kawata, the world of rocks and ice, vigorously self-evident to the point of danger, was “masculine,” and so her art would be.

Kawata’s embrace of a familiar gender stereotype in recounting this key insight is provocative. To see it from her point of view one must bear in mind the highly regimented sex roles of postwar Japan, still tradition-bound; and then we must picture Kawata, in complete disregard of those roles, changing into overalls in the men’s locker room of a large Tokyo glass factory. Kawata’s was the unprecedented act of a real-world feminist pioneer, and it came about like this: After graduation, Kawata was the first woman to be offered a job as artist-designer at the factory. Knowing that she would never earn the respect nor cooperation of the craftsmen on the factory floor if she went to work in women's clothes, which were secretaries’ clothes, she outfitted herself accordingly––and, as there was no locker room for women, she simply changed with the men. Kawata’s assertion of common sense was part of a righteous generational change so total (in mindset, if not reality) that most of us can hardly imagine the world before. The withering away of patriarchy––some part of it––took place because Kawata insisted on overalls; and by and by, as the glass workers began to implement her designs with enthusiasm, the withering quickened.

With this perspective we can now see how Kawata’s “masculine” artistic goals, deeply influenced by the rigors of minimalism, would be equally open to the subversive, scavenging humor of Dada and arte povera and the biological nuance of Eva Hesse. The safety pin tubes mentioned earlier, the ones that suggest serpents and phalluses, exemplify this mixed lineage. One installation, Grove (2008), is a grouping of upright, cone-tipped cylinders. The artist claims she was thinking of burgeoning bamboo shoots, but the forms also evoke a secret lingam chamber in a Hindu temple, or alternately, a glamorous display of dildos at Toys in Babeland. Though Kawata’s phalluses don’t burn with the compulsion of the animated blobs of Louise Bourgeois or Yayoi Kusama, her comparatively elegant protrusions serve something like the same end: to overwhelm the macho with a proliferating, fertile logic of growth––with the feminine principle, one is tempted to say. At any rate, the choice of material for Kawata’s intricate phalluses performs its own critique: for the safety pins, of course, are ironic emblems of “women's work,” the tending to babies and the hemming of hand-me-downs. For that matter, women's work has just as much consisted in churning out cheap factory goods, such as safety pins, at cruel, unequal wages; Kawata’s shiny “metal” may well have been spun by female labor in mills every bit as dark and Satanic as in Blake’s day. And we might also notice that Kawata’s phallic towers comprise numerous little “pricks,” a nasty, belittling slang usage compared to most such epithets––which makes one wonder if “prick” might be the by-product, itself, of women’s work, whether via nursery or factory.

Returning to the installations at Kentler, we may look at Kawata’s choice of cardboard with renewed curiosity. Does it, too, have hidden meanings? Are her black-and-white stripes in Vertical Sound calibrated to challenge, however graciously, the quarrelsome opacity of Frank Stella and Daniel Buren? Or the priestly solemnity of Barnett Newman and Agnes Martin? As for the second work, Rhythm, Kawata has sectioned cardboard into lacey girders and arranged them to glimmer and refract like the surface of a lake. You could read these supple trusses as a feminist deconstruction of the skyscraper; or as the healing reconstruction of a lost pair of them. I offer these suggestions, but you may have your own. The important thing to appreciate is that no matter how powerful the evocation, function always follows form in Kawata’s practice––any and all imagery emerging from a neutral substrate of permutational tinkering. From there, Kawata works her way up to high altitude, step by patient step.

––David Brody

David Brody is a painter and digital animation artist living in Brooklyn. He teaches art at MICA in Baltimore and SVA in New Yori City, and also writes reviews for Artcritical.com.