exhibition

Elaine Smollin, Drawings from Palisades

Scenes from the Life of Charon

Date

March 30 – May 6, 2007Opening Reception

March 30, 2007Artist

Elaine Smollinexhibition Images

Click to Enlarge.

Press and Promotion

About the exhibition

ELAINE SMOLLIN

Drawings from Palisades

Scenes from the Life of Charon

A short drive north of New York City lies the small town of Palisades, named for the nearby line of lofty cliffs that overlook the Hudson River on its western bank and merge with the Hudson Highlands to the north. Part of the same dramatic topography that provides New York with its uncommonly deep harbor, these unbuildable cliffs guarantee scenic overlooks to motorists for miles along the eponymous parkway through northern New Jersey and New York’s Rockland county. The word also refers to a barrier or fortification made of closely-spaced stakes or pales. This conflation of geological and technological vocabularies, of nature and culture, resonates in the drawings of Elaine Smollin. Working in this unprepossessing upstate hamlet for the last three years, Smollin has developed an extraordinary fusion of her interests in archetypal narrative, material culture, geology, philosophy, and art history, while capturing the drama and expansiveness of this landscape in her remarkable project, Drawings From Palisades.

As a graduate student at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn in the late 1970s, Smollin absorbed the thinking of John Dewey and Suzanne K. Langer, and those philosophers have remained central to her attitude toward the nature of aesthetics, and toward her own art. Dewey, in Art as Experience, describes activity of the beholder as that of reconstructing the art object in his or her own consciousness, a prerequisite of perception; Langer recognized, in “symbolic transformation”--the penchant humans have for impractical means, such as music, poetry, and art, to come to grips with our experience--evidence of a deep-seated and rational need for those forms. The political ramifications of the individualism both viewpoints imply, and their suggestion of a kind of psychic borderlessness, have influenced Smollin ever since, informing her study of film theory at NYU Film School, and, more recently, of archeology.

Concurrently with her formal art training, Smollin worked at the Robert Elkon Gallery in uptown Manhattan, and had frequent, close contact with work by Willem de Kooning, Joan Mitchell, and Arshile Gorky. The extraordinary sensitivity of these artists to the expressive potential of their chosen medium made a lasting impression, as did the varying degrees to which their imagery suggests the mythic dimension of figuration. But her art historical references include giants of the Western narrative-figurative tradition, especially Tiepolo, Dürer, and Michelangelo, from which Smollin often quotes directly. Her enthusiasms also embrace Chinese Buddhist painting, a tradition in which the autographic mark, that badge of individual sensibility, asserts itself even while tethered to the depiction of boulders and foliage, flora and fauna.

In 1991, Smollin was employed at the excavation of New York’s African Slave Burial Ground in lower Manhattan There she absorbed the methods and theory of that profession, as well as its parlance, for example the “matrix” which refers to the three-dimensional axis on which excavations are recorded. The artist was immediately attracted to the field as an outlet for her considerable drawing skills, and grew to love it for the opportunity it presented to reconcile naturalism and metaphysics, the way in which the material artifacts the archeologist renders suggest, even in their fragmentary, residual state, the relations between mortals and gods, flesh and the spirit. From this experience she has recast the Charon figure for her drawings, not as a monstrous harbinger of dread but of a man disillusioned and yet compassionate.

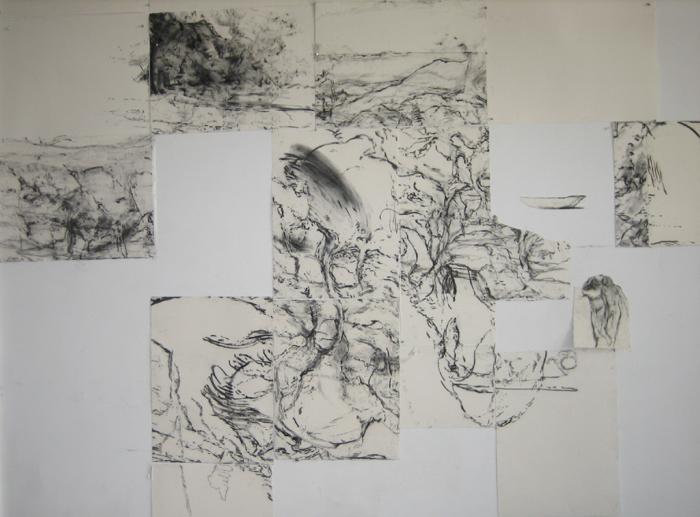

Hugely important to the course of Smollin’s visual thinking was an autumn spent drawing in Prague’s ancient, basin-like Loretta Orchard, an experience that allowed her to sense the “volume” of the landscape, and prompted a desire to elaborate on that vision. Thus it was that two years ago, in May 2005, Smollin broke out of the traditional rectangular format and began to approach her drawings’ supports—large sheets of heavy, rough watercolor paper—as modular units that could be repositioned and recombined at will, in response to compositional contingencies as they might present themselves. A salient characteristic of Drawings From Palisades is this symphonically expanded format, which, in its graphical fluidity and procedural flexibility, suggests the body’s movement from point to point through the landscape, and mimics the mind’s movement through allegorical space as it leaps from thought to thought. Any of these component drawings could stand alone as a self-sufficient artwork; in aggregate they form a panorama as if viewed from shifting vantage points. But Smollin is no cubist. By disassembling the picture plane, she does not fragment space, but, emphasizing the interchangibility of form and void, plenum and vacuum, near and distant, unifies it.

The artist has investigated the optical characteristics of charcoal for thirty years. She now makes her own, an operation that results in a dish of little black shards in which, working in the field, the artist identifies her dusky palette—the range of black and the differing tactility of carbonized cherry, elm, willow, and birch—not by sight, but by touch. As a result of Smollin’s process, the paper she works on is as visually prominent a component of the final work as the charcoal she applies to it, with a touch that veers from raspy to velvet and yields tonalities both delicate and forceful. From this matrix of strokes emerge the suggestion, sometimes faint and sometimes not, of human figures, animals, vessels, as well as the rocks and trees that have been the iconographic bedrock of landscape representation for centuries. Smollin’s drawings bear their intellectual burden lightly, buoyed rather than encumbered by the artist’s breadth of study, travel and experience. This is because, having mastered her deceptively simple materials, she graciously and confidently allows them their distinctive voice.

–Stephen Maine