exhibition

Hedya Klein, Still A Life

Date

October 10 – November 9, 2008Opening Reception

October 10, 2008Related event

Hedya Kleinexhibition Images

Click to Enlarge.

Press and Promotion

About the exhibition

Hedya Klein’s drawings are delicate and intimate. Painted in gouache, inks and acrylics on paper, they have a small scale that could indicate preciousness or fragility. But the focus on biological (both floral and faunal) processes speaks to the strengths and persistence of the basic impulse for life. Her details, though simple, are so numerous and complete they make excellent building blocks for larger more complex forms.

Klein uses just a few colors against empty white expanses, but they are intense and highly saturated. They glow with vibrancy against the white paper, reading like carefully collected specimens on biological slides or early photographs aiming to classify and celebrate the grand diversity of nature.

Klein’s figures, however, are not all strictly accurate. Many are fanciful conglomerations of biological forms. She draws “bees” that are faceless and fuzzy. They seem to be almost vegetal, like hairy acorns or seedpods, save for their delicate pairs of wings that allow them to hover in mid-air. Other forms look like pollen or algae or segmented cacti. With simple lines, she finds a detailed variation of surface texture and shape. We trace her plants, with linear green strands, through segment after segment that seem to have formed by osmosis or budding. These simple ropy shapes culminate in the flowers at their tips. In the flowers, which are pink next to the green strands, darker red seeds swell and prepare to drop, beginning the cycle over and over again.

Klein’s observational program isn’t limited to the biological. She chooses a variety of idiosyncratic items from her surroundings, and those have included international locales in Croatia, Israel, Holland and Austria. Aside from seedpods and mushroom caps and shark eggs there are balloons, plastic bags and ornate chandeliers. / All of her subjects are examined with the same meticulous fixation on detail. One persistent theme is a crown shape based on a balloon popular at Dutch festivals celebrating the monarchy. It looks like a piece of twisted coral or some fossilized relic of prehistory when Klein represents it. Its swollen but slightly limp members seem hampered by age, frozen in pale blue and teal shades, worn down from a lost period of vitality. There’s a maudlin sort of disconnection between the implied piece of royal raiment and its clumsier, soft, mass-produced form.

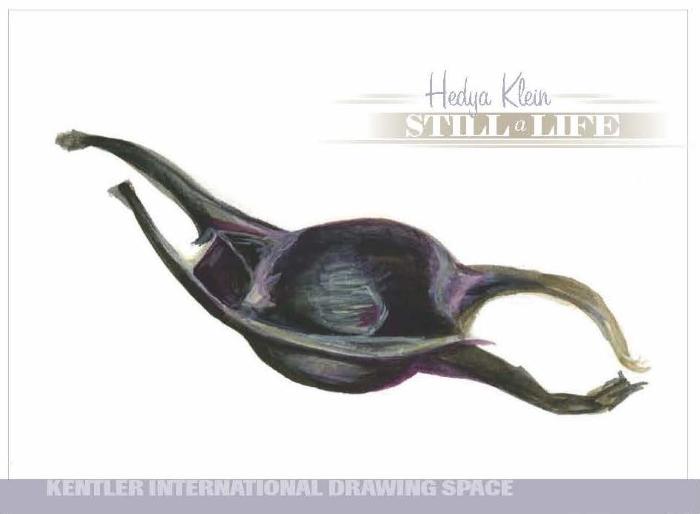

The focus on vital processes of course has its counterpart in death, as Klein reveals in a compelling series of studies of a bat carcass. What sounds morbid is instead fascinating, evincing a mix of scientific detachment and emotional empathy for this bizarre mammalian cousin. Found collapsed in a barn, its dark-adapted body becomes a source for drawings on many scales, each emphasizing a different view. Klein repeatedly finds the vibrancy in its deflated, desiccated features.

The bat has a head and four limbs, but those limbs are the armature for the flaps of skin that formed its wings, and that head is tiny, with out-sized eyes and nose and ears and teeth. These exaggerated sense organs are all adapted toward a nocturnal life of insect eating. It’s both a beautiful creature and a fascinating monster, and Klein captures its complexity in faded shades of gray, blue and brown.

Intimate work such as this is well suited to the scale of an artist’s handmade book, and Klein has used silkscreen to create one that reads almost like an animator’s flip-book. Turning the sturdy card-stock leaves, one witnesses orblike clusters of cells in Day-Glo chartreuse. The shocking color makes the delicate lines seem filled with vibrant fluid. The silkscreen process assures that the lines, though weblike, are whole, unbroken and precisely affixed to the paper. Klein has cut the paper before binding so that some images are bifurcated, seeming to flip over to the other side, some sliding out of the frame altogether. A sense of movement and flow is thus created, and whether we see a swift river or an internal vein full of plasma, the inevitability of the cellular reproduction is compellingly captured. The olive-drab cover for this book, and the handheld scale, belie the rewarding surprise of peering inside and “reading” the green images as they evolve.

That animation instinct is perhaps a natural impulse for Klein, who has made a short animated film, which makes literal the movement that is implied by all of her drawings. In her video, delicate lines track a path broken by dots and dashes. As it flows, spores of multiple cellular pockets blow by. From a mass of tangled hair, strands are expressed and blown by the wind. They create concentric spirals of seeds, which pulsate and revolve. A mound of tubers grows into prickly cacti, whose follicles writhe and shimmer until they’re shot from their hosts like tiny darts. Other flowers grow and swell from above, and their spores are dispersed by one of those faceless bees who drifts by clumsily.

Tangles of protozoa seem to proliferate from all sides. Klein is adept at using every aspect of the white frame to situate her small creations, as when another tangle of hair explodes from all sides to congeal in the middle. When the spores fill the frame they begin to knot themselves into an organized weave. The original clovelike spore rotates back into view and spins for our pleasure, showing off in a final sparkling flourish. By the end of the video jellyfish-like creatures are emitting sperm drops into the empty sea, which frolic like tadpoles and then wither and die.

But the cycle begins again, and that harnessing of natural energy, in endless patterns of excitation, exhaustion and renewal, might be the basis for all of Klein’s drawings. Even a series of studies of electrical windmill towers fits into this context. Though mechanical, the towers have a natural function and a smooth ergonomic design that seems in harmony with the lack of waste on display in Klein’s economical work. To her, the world is a packed and infinite resource of renewable growth. One that requires only gentle, responsible stewardship to perpetuate.

- Shawn Hill, Shawn Hill has been writing about art in New England and New York since 1990. He received his master’s degree in art history from Tufts University in 2000. He began teaching at Montserrat College of Art in 2003, and his regular classes are Art Since 1945 and the History of Photography.