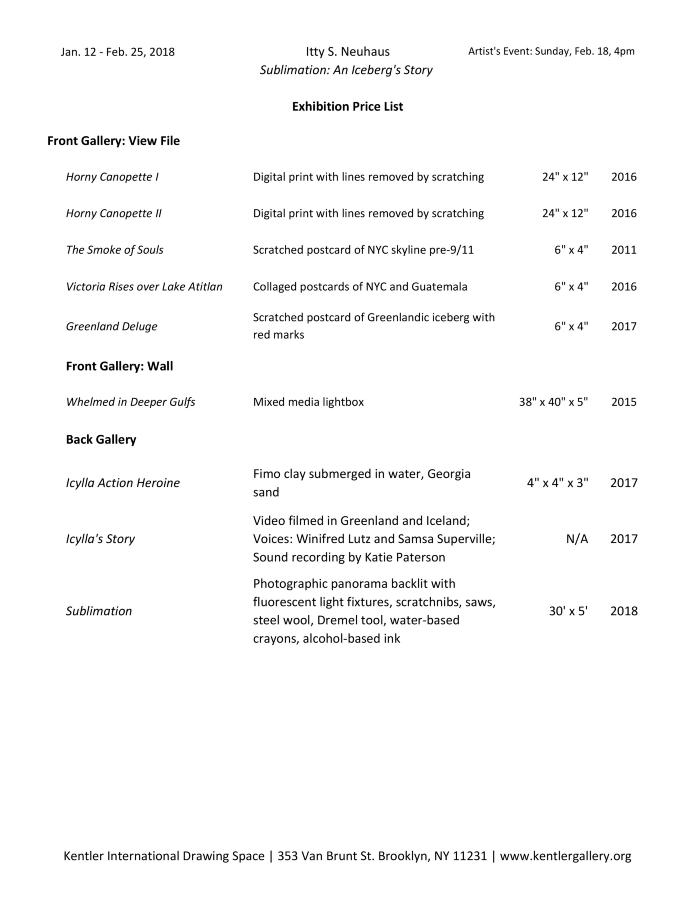

exhibition

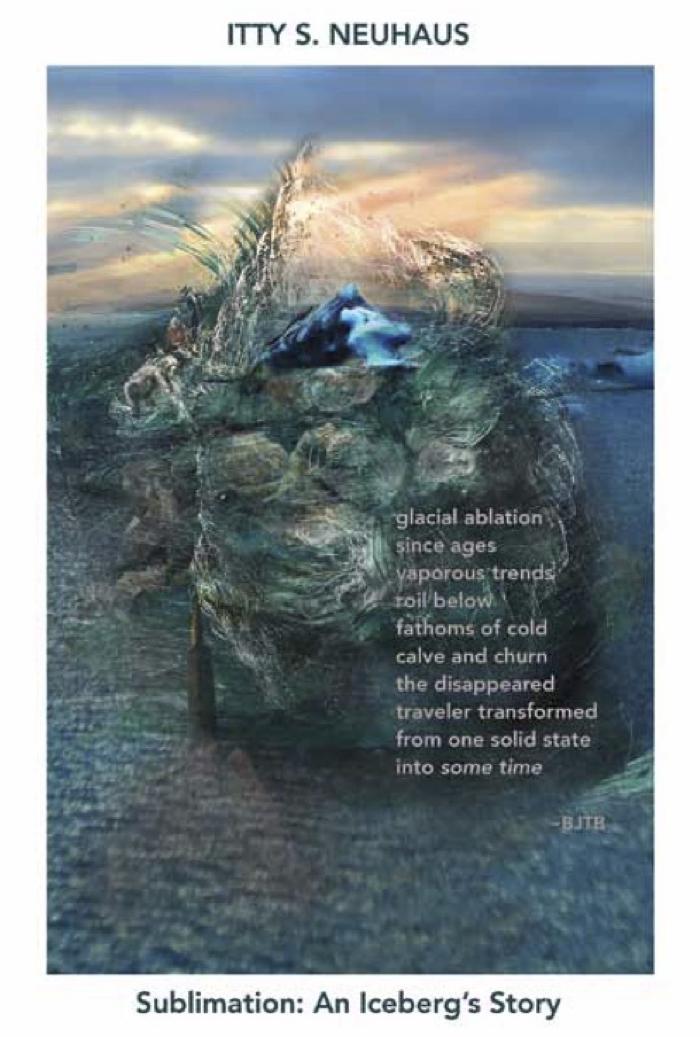

Itty Neuhaus, Sublimation: An Iceberg's Story

Date

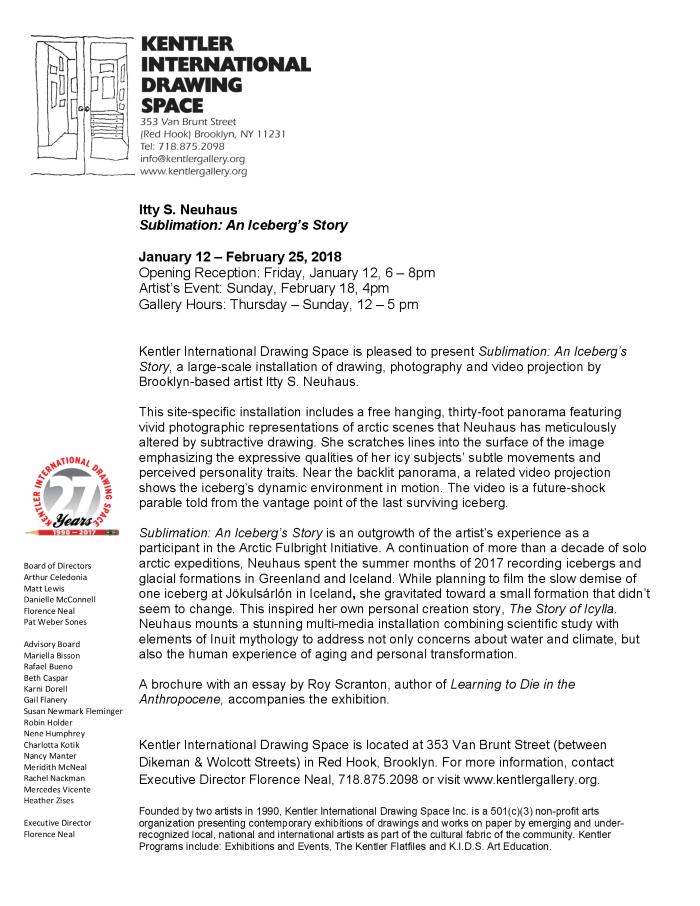

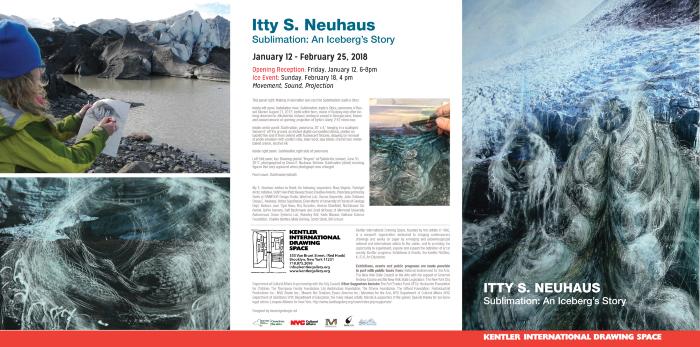

January 12 – February 25, 2018Opening Reception

January 12, 2018Related exhibition

Focus on the Flatfiles: Water ReflectionsRelated event

Ice Event with Itty Neuhausexhibition Images

Click to Enlarge.

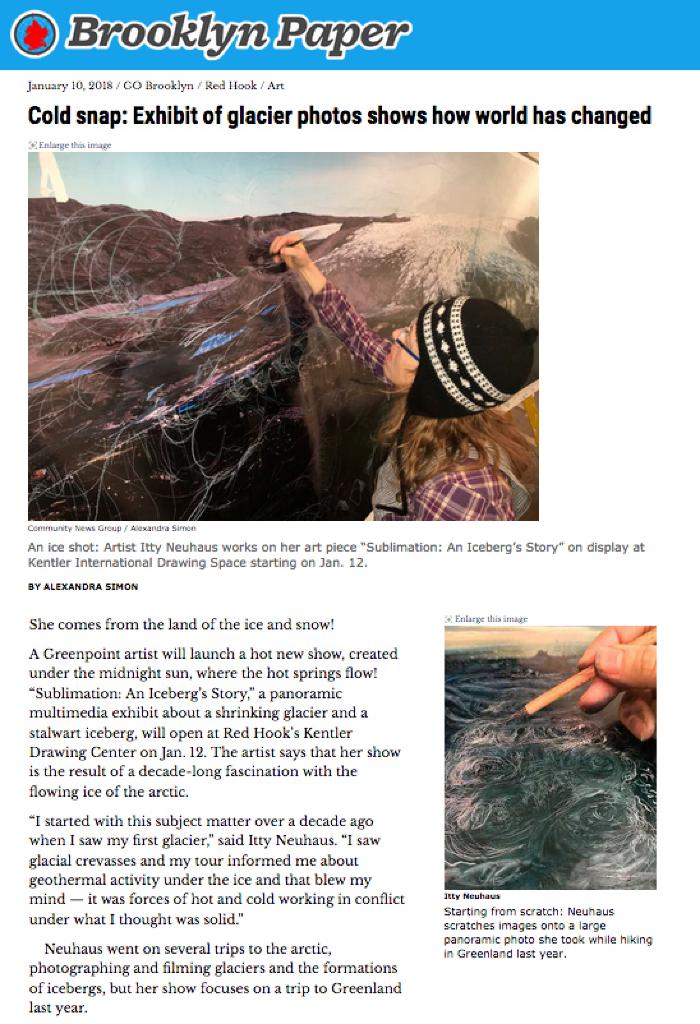

Neuhaus at work, subtractive drawing on 30' panorama photo of Russell Glacier in Greenland. Photo credit: Alexandra Simon

Press and Promotion

About the exhibition

Strange Snow: On Itty S. Neuhaus’s Sublimation

by Roy Scranton

The first snow of the season is falling as I write this, coating the world outside in granular, crystalline layers of white precipitation, frozen water wafting from the sky, so simple, so taken for granted. The first snow is always fresh, always refreshing, even as it comes later and later each year, but this one is especially exciting because it is my daughter’s first. Through her new eyes, the world fills once again with wonder. By the time she is twenty, though, such snows may be no more than a memory. As she has her first snow, so will she have her last.

Things are different in the Arctic. Even after the poles thaw and the permafrost melts, the winters there will surely still be cold enough for it to snow sometimes. Perhaps my daughter will visit the icy north as a tourist, like her father did, to see the last dwindling glaciers of Greenland before they melt into the sea. If she’s lucky she just might. If she’s lucky there will still be tourism.

The snow descends through the dark, leafless branches of the trees, glinting like mica in a cobalt sky and whirling through vortices of bruise-yellow streetlamp light, fluttering wild like the blown-out down of a buckshot duck. A leading story in my twitter feed proclaims “The most accurate climate change models predict the most alarming consequences.” In Kangerlussuaq, Greenland, where the sun will shine for only two and a half hours today, it is ten degrees warmer than it is in Indiana, where I write.

As an independent observation, this means nothing. Weather is not climate. Experience is not reality. Global warming is not watching the snow fall in Indiana, or ice melt in Greenland, or wildfires burn across the hills above Los Angeles, or floods drown Bangladesh, but all of it taken together at once, along with the history that brought us here and the ramifications echoing thousands of years into the future. Reality is a composite of here and there, then and now, subjectivity and fact. Reality is a haunted palimpsest, a photo etched with future ghosts. Reality is a flickering projection.

Itty Neuhaus’s Sublimation connects Red Hook, Brooklyn to Greenland, here to there, then to now, in ways that subvert and complicate our typical thinking about the Arctic’s spectacular doom, the sublime threat of melting ice, and the planetary apocalypse we call global warming, all of which we have become so used to that they seem conventional, even boring. How many news stories saying we’re fucked can you read? How much apocalypse can you stomach? It is an astonishing world to live in where icebergs the size of Manhattan calving from a glacier’s face can seem tedious and the end of human civilization banal, #so2016, but such is our state, benumbed by our screens, drunk on our own despair. Sublimation dissipates this fog to help us see anew.

This is the purpose, as I see it, of art. Viktor Shklovsky wrote in “Art as Device[BC1] ” (1925):

In order to return sensation to our limbs, in order to make us feel objects, to make the stone feel stony, man has been given the tool of art. The purpose of art, then, is to lead us to a knowledge of a thing through the organ of sight instead of recognition. By “estranging” objects and complicating form, the device of art makes perception long and “laborious.” The perceptual process in art has a purpose all its own and ought to be extended to the fullest.

Global warming, and our apprehension of it primarily through mass media, presents a peculiarly difficult object of knowledge, so much so that Timothy Morton has coined the term “hyperobject” to help make sense of it. A hyperobject is an object so large and multifaceted, so massively distributed in space and time, that it is impossible to grasp in any one manifestation.

If the problem of art is how to make the stone feel stony, then the problem of art vis-à-vis global warming is how to make it massive, uncanny, sad, and disturbing again, how to make the grief real again, how to reframe our participation and complicity in its unfolding, how to make our perception of it “long and ‘laborious’ ” instead of quick and facile. Sublimation achieves its effect through the ghostly etchings of eco-tourists and snow flurries haunting the glacier face near Kangerlussuaq, through the uncanny story of Icylla, an iceberg who doesn’t want to leave her glacier, which evokes the eerie power of Inuit folk tales, and through the estrangement and reframing of space and time itself in the work’s bifurcated form.

In the Inuit legend of Sedna, a young woman is tricked into marrying a sea bird, but when her father rescues her, he throws her over the side of his kayak into the frigid Arctic sea. Sedna grabs the kayak in desperation, and her father chops off all her fingers, which fall into the icy water and become the sea mammals upon which the Inuit depend for food: seals, walruses, whales. Her bloody stubs freezing, Sedna slips away and sinks to the bottom of the sea, where she becomes a mighty goddess, with power over the waves, the ice, and the animals that had been her fingers. Sedna’s power comes from her sacrifice. Through a moment of brutal and enigmatic violence at the limit point where the human world meets the sea, Sedna leaves humanity and becomes a goddess, transforming from matter into spirit. Sublimation likewise tells the story of our own world’s transition, and the work’s subtly estranging power comes from Neuhaus’s tender evocation of humanity’s brutal and enigmatic violence against that which we persist in calling “nature,” but which is in fact ourselves.

The snow lies crisp and frozen outside my window. Our gas furnace cycles on, blowing heated air throughout the house. I can hear my daughter wake upstairs. Somewhere far away, an iceberg shatters into the sea.

- Roy Scranton is the author of Learning to Die in the Anthropocene and the novel War Porn, has been awarded a Whiting Humanities Fellowship and a Lannan Literary Fellowship, and currently lives in Indiana.