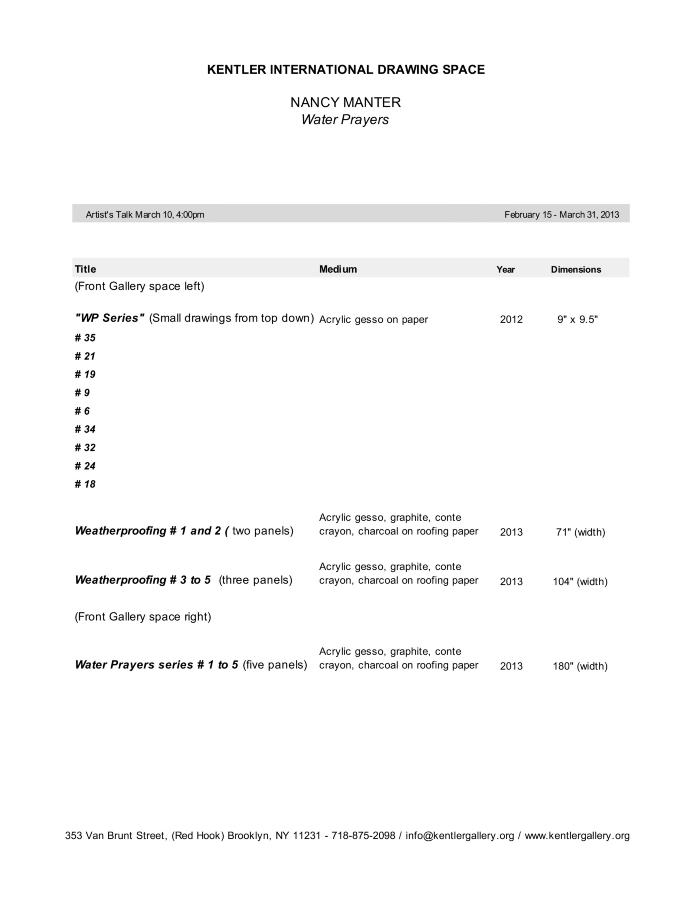

exhibition

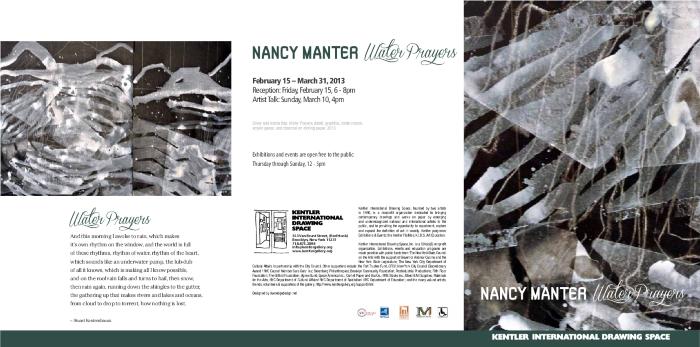

Nancy Manter, Water Prayers

Date

February 15 – March 31, 2013Opening Reception

February 15, 2013Essay By

Stephen MaineArtist

Nancy ManterRelated exhibition

Selections from the Red Hook ArchivesRelated events

CARE for SANDY: Red HookArtist's Talk: Nancy Manter

exhibition Images

Click to Enlarge.

Press and Promotion

About the exhibition

Solo exhibition, front gallery space

Artist's Talk: February 19, 2013

“Whenever people talk to me about the weather, I feel quite certain that they mean something else.”

—Gwendolen Fairfax in The Importance of Being Earnest by Oscar Wilde

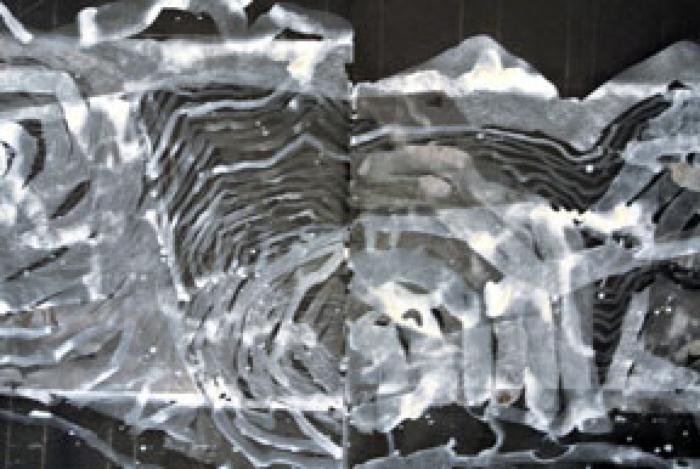

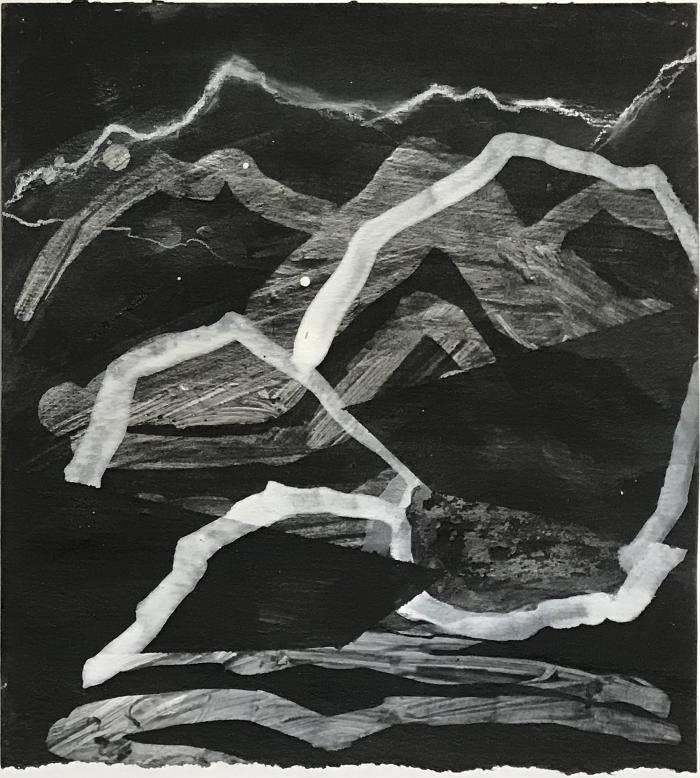

For Nancy Manter, as for many artists, drawing is distinguished from other mediums by its directness. The work in Water Prayers, then, qualifies as drawing not because it is on paper, its approach to organizing visual information is predominantly linear or its palette is achromatic, but because of the directness with which Manter handles her materials. Many of these drawings were executed in acrylic gesso on roofing paper. Gesso is a fundamental studio material, formulated to provide a pure white ground when brushed over stretched canvas or linen, and a barrier between those vulnerable fibers and oil-based paint. It is not intended to be diluted much, but Manter does just that and, with brushes, rollers, sticks and her hands and feet, applies the thinned white liquid over a near-black ground.

The stiff, rough, slightly shiny roofing paper is the perfect substrate for Manter’s process. It is moderately absorbent, allowing the artist to achieve a range of atmospheric effects—diaphanous washes, gauzy films of subtly modulated gray—but tough enough to hold up where the application of gesso approaches impasto. For Manter, however, roofing paper is not just a material suited to her creative needs. Mindful of the real-world implications of her work, and attuned particularly to the form-giving potential of weather, she plays on the material’s associations as a membrane between the indoors and the outdoors, as a metaphor of protection, a symbol of our attempts to provide ourselves refuge from wind, rain, cold. On this psychologically charged surface, the artist enacts a meditation on the elements of nature.

Manter did not give up on gestural abstraction while it was out of fashion, but instead found things to do with it that are distinctly her own. This former ballet dancer and downhill skier thrives on movement, and is fascinated by its ephemeral traces. Her work has always been embedded in landscape, often literally. She has made temporal drawings (captured in photographs) with her footprints by tramping through mud, dew and frost, and in snow with the tires of her car, and with her skis. She has made drawings in the condensation on her car’s windows. In these projects, mark making is not an existential struggle with the void of the blank canvas, and still less a means of description or representation, but a kind of first response to the urgent condition of being present in the landscape, in the weather.

The panoramic landscape as virgin territory is a well-worn theme, and has long been obsolete—at least on Earth. In her studio, Manter has a book of NASA photographs of the lunar landscape, taken by man or machine from the satellite’s surface. She loves them for the stunningly beautiful range of whites and warm pale grays that depict the rocks, craters, smooth seas and distant hills arrayed against the inky blackness of outer space. The photos’ formal similarities to her roofing-paper drawings are striking, including the way both are composites of multiple views or visual fields. In a few of the photos you can even make out the surface module’s tire-tracks in the dirt, or an astronaut’s footprint.

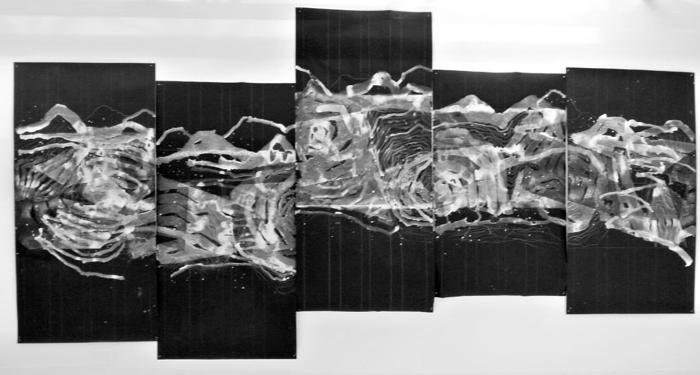

The largest work in the Water Prayers exhibition, Water Prayers, the same title as the show, is made of five vertical sections of different lengths, which are contiguous along their sides but form an irregular top and bottom edge. If the sections’ nonalignment connotes instability and displacement, it is countered by a strong unifying element that traverses the five sections and visually reconciles them along a horizontal axis: a gorgeously stormy band of brushy, loosely concentric circles, oozing washes and pooling white runoff —underscored by a flurry of fine lines in white pencil—that evokes mounting waves and swirling water.

The devastating effect of Hurricane Sandy on the New York/New Jersey metropolitan area generally, and particularly on the Red Hook neighborhood that Kentler International Drawing Space calls home, is not very deeply hidden in Manter’s weather-related dialectic of stability and disorder. That epic storm also contributed to the growing awareness of global climate change, and prompted public officials to acknowledge that fact’s relevance to plans for redesigning and rebuilding the urban infrastructure. In these circumstances,

Manter’s Water Prayers series is both site specific and time specific; in Red Hook, that time is called “post-Sandy.”

When rough weather hits, you take cover. It’s a reflexive reaction, a spontaneous act rooted in the instinct for self-preservation. From a local perspective, extreme weather comes and goes. We experience at first hand only a small part of the system. The storm will move on, and life will continue as before. But what if shelter is inadequate, services disrupted? What if the storm is here to stay, a permanent change, the new normal?

Ideologies attach to art of any kind, including abstraction. Manter’s project, while both profoundly personal and alert to the potential of unassuming materials, is neither wholly autobiographical nor purely concrete. It expresses an attitude toward the world, predicated on a belief in the efficacy of images in conveying meaning. That worldview, it seems to me, is a hybrid of curiosity and caution. Manter is curious about conflict—in fact, she relies on conflict of various kinds to give rise to the drama, the pictorial momentum, in her work. Her exploration of landscape, for example, hinges on the disparity between her memory of a particular locale and her present experience of it. She once told me that a “bad weather day” is a good day for her. These are productive disruptions.

Destructive disruptions are another matter, however. While an artist’s social function is not to provide solutions (to global warming or anything else), having his or her finger on the pulse of our collective aspirations and apprehensions, hopes and fears, makes it possible to develop critical imagery—imagery that takes up a position in the great public debates of our time. As an artist, Nancy Manter is primarily concerned with the exigencies of picture making. But while her pictures might talk about the weather, they mean something about the interdependence of individuals, memory as critique and the fate of the planet.

—Stephen Maine

Stephen Maine is a painter and art critic in Brooklyn, New York.